Here stands a musical great, whose intricately rhymed lyrics once embodied the violence, sacredness and obscenity of poor white America, in the form of a 50-something running around in an embarrassing superhero costume.

Johnny Cash began the 80s as a Country Music Hall of Fame inductee, and ended the 80s as a Bible-studying hasbeen, dropped by his label and playing Greatest Hits sets. In between was “The Chicken In Black”, a single which orthodox Cash scholars use as shorthand for the nadir Cash was saved from. Cash later claimed the single, a rhyming monologue about a mad scientist replacing Johnny Cash’s brain with a bank robber’s, was an intentionally bad song made to evade a record contract, but this was a revision. He was excited about the project to the point that he had an entire superhero costume made for his new alter-ego, the Manhattan Flash, and you only start putting on primary-coloured Spandex if you know what you’re about.

“The Chicken In Black” was remarkably commercially successful for Cash by that point. It managed a respectable #45 on the Billboard Hot Country chart, only tanking after Waylon Jennings ridiculed Cash for his costume, and Cash cringed a cringe so complete that he demanded the video pulled from rotation, and that was the end of it.

Cash knew a good funny song when he heard it — nobody would argue with “A Boy Named Sue” — and he knew the novelty of “The Chicken In Black” is in the service of expressing the intensity of Cash’s pain, both as an older artist searching for redemption and as an older artist in a body falling apart (by this point, his painkiller use was never for fun). Cash’s body, we’re told in the song, has ‘outlived [his] brain’ — a potent metaphor for an artist who has been going so long that he’s exhausted all of his great ideas, but then kept making music, because life is so longer than youth is. Cash finds the brain so vestigial that, even after its replacement with a bank robber’s, Cash doesn’t notice much different, except he can’t sing the way he used to, and the garish Opry shows he’s trotted on to do his old hits on are conflated with a compulsion to steal money from his audience. Even the name of his robber alter-ego, The Manhattan Flash, evokes a showy urban huckster completely disconnected from the isolated agricultural lands where country music first emerged. The final insult is that the spring chicken that ends up with Cash’s brain transplanted into its head, like a young artist raised on the classics, is now putting on an acclaimed show that Cash acknowledges is better than anything he can do. And all of these layers come from a beautifully rhymed, genuinely funny novelty that uses its imagery of comic book cops-and-robbers to let a now-showbizzy Johnny Cash use his traditionally violent subject matter without having to cap.

Anyone who likes novelty rap songs about old guys in superhero costumes should be disappointed that Cash balked. But balk he did, and opioids he did some more, until Rick Rubin peeled Cash out of his yellow Spandex, placed a guitar in his hand and Trent Reznor’s prayers on his tongue, and conferred upon Cash the blessing of cool, a timeless authenticity that emerged from Cash’s decrepitude and not despite of it. That’s the legendary version of the story, at least, and that’s as much as I need to go into. If you want the truth about Johnny Cash’s renaissance, try reading some weird Johnny Cash book that starts off the part about “Folsom Prison Blues” with an analysis of “My Name Is”, or something.

“Houdini”, Eminem’s unusually well-charting 2024 comedy single where the 50-something-year-old artist is running around in a superhero costume in the video, is Eminem’s first lead single for a non-compilation album since “Walk On Water” seven years earlier – a Rick Rubin-produced grandeur record, an attempt to exploit Eminem’s advancing age to pull a towering megastar down to a level where artistic expression was once again possible.

“Walk On Water” is a self-contradictory record. It’s evoking minimalism, with the lack of drums and the photorealistic vocal recording that lets us hear Eminem moving around his microphone, but it’s also gussied up with Beyoncé and orchestral strings, pop concessions for an artist who was a far more mainstream prospect than Cash had been by the time Rubin recorded him singing “Delia’s Gone”. It’s exactingly penned, even to the extent of incorporating precision inkblots (“pressure increases like khakis”) to remind us of Slim’s abjection, and yet the combination of the crafted syllables and the Shakespearean performance amounts to a humblebrag, a flex of Eminem’s genius even as he feigns having lost it. “Walk On Water” is a funny record — Eminem’s grunts and swears as he crumples up his endless sheets of paper are done with the same comic timing as the gory sound effects he adlibs after his lyrical Tex Averyisms. It’s funny like the scene at the end of Withnail And I is funny, with Richard E. Grant performing Hamlet to the wolves. But it’s not, you know, funny. It’s not funny like the old stuff is. It’s not funny seeing that ex-brat, smothered by dark clothes, dark hair and a dark beard that never seems like part of his face, gripping the microphone with a shaking hand vined from years of weight training, telling us that all this obsessive cultivation over himself gave him is the ability to leave us longing for a time when he was too fucked up to have control over what he was doing.

“Once, about 6,000 years ago, Eminem sounded genuinely playful,” wrote Jayson Greene in a pan of “Walk On Water” for Pitchfork. “I’m interesting! The best thing since wrestling!” Today, gaunt and mean-eyed1 and forever so fist-clenchingly serious that he seems on the verge of squinting himself into a black hole, Marshall Mathers senses, maybe, that he’s not that interesting anymore.”

The punchline of “Walk On Water” is Eminem, acting out a sudden surge of angry resolve, reminding us, “bitch, I wrote “Stan”!”. The composition itself is trying to remind us of this; a song so beautifully made that even hip-hop non-listeners can tell, a central image of drowning in water, the escalating angry-letter rant verses made cosy and ironic by the warm female voice on the refrain. The problem is that an Eminem who remembers he wrote “Stan” is, as Greene observed, an Eminem who is choosing to forget that he wrote “Without Me”.

The problem Eminem has, the problem Johnny Cash didn’t, is that he was running around in a ridiculous superhero costume in the old shit that everyone liked. The Rubinised Cash was a signal to listeners of a return to the roots, which wasn’t quite true, but the myth felt true enough for the audience’s purposes; the Rubinised Eminem is a false memory, a worthy craft-purist who never fucking existed. The generation who’d once had to hide Eminem’s CDs from their parents were now young adults confronted with a man that reminded them of their parents, and many took it as an unwelcome reminder that they were old and boring now too.

Scarred by the negative response to a song he and his team clearly believed to be artisanal-quality award bait, Eminem released his next two albums and album-length deluxe as surprise drops with no advance promo. On Paul Pod in 2022, Em fumed at his manager that running album promo only gave people more opportunities to decide his music sucked without even hearing it:

“I feel like, [by doing rollout,] you give people time to think and say, ‘well, he better have a song like this or I’m not gonna listen to this shit — he better not have a song like this because I ain’t listening to that shit, that shit’s trash’. It just depends on what ears you sit down to listen to music in!”

Eminem never formally swore off ever doing album promo again, so it’s not that he went back on his word by putting out “Houdini” in advance of The Death Of Slim Shady (Coup De Grace). (It wasn’t even his first lead single after “Walk On Water” for Revival — that was “From The D 2 The LBC”, the lead single for Curtain Call 2.) What was more surprising was that he put out the titles of the album and song in advance — the exact thing Eminem blamed for sinking Revival (when the tracklist leaked, fans saw Track 1 was called “Walk On Water” and Track 2 was called “Believe”, and guessed they were in for a turbo-barfest). The titles themselves were provocative, and the promo cycle was laced with Easter eggs designed to inspire exactly the kind of fan speculation Eminem had complained about. Was killing Slim Shady an abandonment of shock tactics, a return to pre-Dre grimy basics, a retirement album? Was Houdini invoked as a symbol of lyrical magic, an escapologist defying death, or as a slain casualty of a delusional fan who didn’t understand the act wasn’t real?2

The real meaning was the break with the past presented by the fact that Eminem no longer cared if a huge chunk of his fanbase was going into his work with their expectations too high.

It’s possible that Eminem’s confidence wasn’t higher because he was sure, but because, by 2024, the bar was set lower. When Eminem put out “Walk On Water” in 2017, he was coming off the back of Recovery and The Marshall Mathers LP 2, both of which netted Best Rap Album Grammys and got positive reviews from mainstream critics (though not the hipper blogosophere outlets — Jayson Greene’s 2.8 review of Recovery for Pitchfork and Tom Breihan’s merciless savaging of The Marshall Mathers LP 2 for Stereogum showed that tastemakers had turned on him). When the YouTube chart music parodist Mark Douglas put out his spoof of Eminem’s “Not Afraid” in 2010, even following the mixed reception of Encore and Relapse, it couldn’t have been a credible spoof without lyrics like “I’m the greatest rapper alive, a fact that’s undisputed, but for some reason, I act like I’m persecuted… I’m not afraid to get really pissed at all my critics who hardly exist”. But Revival’s condemnation forced a reappraisal of the two earlier albums as a dead end of pop hooks and lyrical horror vacui devoid of horror. The viral Eminem parodists of the post-Revival era were Chris D’Elia growling about napkins, Nat Puff contrasting a punkishly queer Y2K Eminem with a gravelly and boorish 2010s version, and Dylan Godfrey’s portrayal of the rapper as an ineffectual palilaliac.3 The Quietus called Em’s Roskilde Festival set, attended by a record-breaking 130000 people, “hard not to feel a little indifferent about in 2018, especially after the misfire of last year’s Revival LP, the latest in a string of highly mediocre albums.” “If Eminem had been eligible a decade ago, I’m sure I would’ve voted for him,” an unidentified Rock & Roll Hall of Fame member told Vulture in 2022. “But to me, his work is less substantial, less interesting, and has aged less well than it would have if we were having this conversation in 2012.”

No matter how many people Revival turned away, in the eternal doomscroll of the 2010s, it was never possible to stop looking — not entirely. While Eminem’s post-Revival albums moved to a harder sound and got warily positive reactions from hip-hop heads, the caricature of Eminem that proliferated for those unwilling to risk being disappointed by his new music was an old white man angry at young Black people for not kowtowing to his brilliance, screaming sixty syllables per second sans saying shit. Eminem’s hits still came regularly, some even with critical acclaim, but with MTV obsolete, little penetrated into the mass audience. Unengaged fans no longer even knew what he looked like, and disliked learning about it when they found out. Rachel Aroesti in The Guardian complained about Eminem’s Pete Rock-tshirt-clad appearance in his 2018 Twickenham show, describing it as “a shock to see how anonymous this one-time master of aesthetic provocation now looks… Gone is any semblance of swagger or attitude, or even humour.” In 2022, comedian Joe Kwaczala, who’d loved Eminem as a kid, told listeners to his podcast Who Cares About The Rock Hall that he and his wife Kristen Studard hadn’t recognised Eminem when he’d come on stage for LL Cool J’s 2021 R&RHoF induction ceremony, at first seeing only a middle-aged man with a beard.

Eminem’s toxic influence on his fans was reevaluated too; his threat was no longer moralistic, but aesthetic, and for the perma-online America, aesthetics are what culture war is fought with. Eminem’s post-Revival years coincided with the pivot to video, generating hours upon hours of podcasters and commentators scoffing at Eminem’s obsessive rhyming, inability to rhyme, overly poppy hooks, inaccessible lack of hooks, flat robotic voice, overemotional screaming voice, inability to change his style, inability to maintain a consistent style, and popularity with crypto-racists who mistook their discomfort with Black people for a hatred of ‘mumble rap’. Gimmicky Facebook rappers not fit to stroke Eminem’s dictionary, many of them white, spunked exhausting hyperspeed gibberish on YouTube, and Twitter users gave them the virality they wanted by blaming Eminem. Some of Eminem’s appointed heirs, already beneath him, became glaring embarrassments: Logic quit rapping for video game streaming and put out an unreadable book, and Joyner Lucas disintegrated into mawkish special-episode songs and insufferable misogyny. In March 2021, a TikTok user named @cassiesmith607 mugged into her camera lens about Gen-Z trying to — wait — cancel Eminem, and became the internet’s shorthand for white Millennial cringe, reverence for Eminem’s lyrical transgressions thrown away with the ballet flats, bacon memes and Deathly Hallows tattoos.

By the way, this is about where I join the story. Y’see, around this point, the negative online rep around Eminem was so intense that I began to think back to the cult around him during my youth and wonder how it was possible that anyone ever thought he was talented at all — had the skin colour done so much for him that nobody noticed his career had been ended by Mariah Carey? I went on YouTube and listened to a bunch of the silly ones, and had a nice nostalgic buzz off them but nothing more, like how the first time you try weed it doesn’t work. Then the day after, I listened to The Slim Shady LP, and the universe shifted on its axis, and eventually I listened to Music To Be Murdered By Side B, and now I’m writing unhinged 5000 word posts about “Houdini” where I haven’t even talked about the music yet. The fact I didn’t get that much pushback from my Eminem-hating peers — many of them sheepishly sent me messages admitting that “Love The Way You Lie” helped them escape a shitty relationship, or that “Not Afraid” helped them stop drinking, or that, although they really only like the early albums and they’re not kidding they’ve really tried OK, they can rap along with “Killshot” off by heart — suggests a lot of this was just driven by fear of being caught enjoying something in public, an age-old problem for any youngish people who base their self worth on the quality of their taste. But a normal person seeing the hate could be forgiven for not bothering to check. Like the Gallagher brothers, Eric Clapton or (God forbid) Moby, the history of popular music is full of quick-tongued straight white men who were geniuses until they suddenly never were.

Somehow, all of this opprobrium was happening during Eminem’s canonisation, an equally dangerous event. Born ten months before DJ Kool Herc’s Back To School party on Sedgewick Avenue, Eminem was 50 years old on the day that hip-hop turned 50, and 2023’s bill of festivals, music documentaries and museum exhibits celebrating the rise of the culture formed a graceful rhyme with Eminem’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction in 2022. Facing criticism due to being a white artist inducted before the pioneers of the art form (Rolling Stone, which made the requisite pseudo-diplomatic description of his talents completely in the past tense, compared it to “[inducting] Kenny G before Miles Davis”), Eminem, wearing 1950s-sitcom-dad spectacles, spent over four minutes of his acceptance speech thanking over a hundred Golden Age hip-hop acts whose work inspired him. When performing a medley of his songs earlier in the show, he’d looked uncomfortable, clinging to his earpiece like a lifeline, but while giving his speech, it was replaced by a breathless pride — not over his own induction, but from having an emcee’s skill so great that he could find the meter and comic timing even in an alphabetical list. It was visible in the way his body rocked at the podium, riding a beat in his own head, just the same as when he’d soothed himself as a little boy by slamming himself rhythmically against the back of his seat.

“I know this induction is supposed to be me talking about myself and shit, man, but fuck that. I would not be here without them. I’m a high school dropout, man, with a hip-hop education, and these were my teachers. And it’s their night just as much as it is mine.”

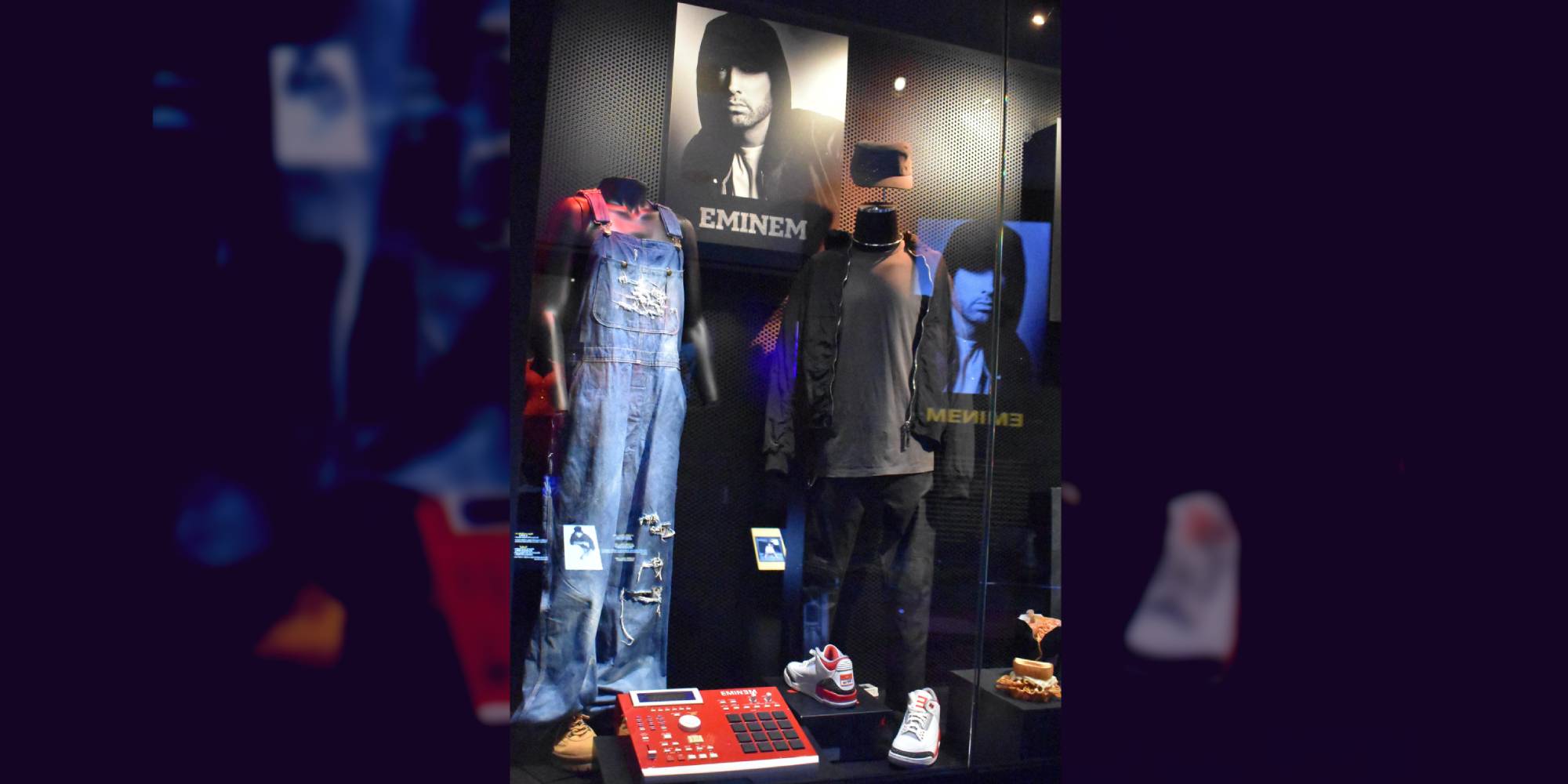

Eminem raised a fist in a salute of solidarity, before rushing off stage to throw his arms around Dr. Dre, like a kid hugging their father after finishing the school play. It’s a shame he didn’t stay to add a 16 to the Dolly Parton-led Super Jam about killing that fucking bitch Jolene, but it probably wouldn’t have worked. His exhibit at the Hall showed his 2000 Anger Management Tour overalls and hockey mask, the Akai MPC 2000XL on which he programmed beats for The Eminem Show, his 2022 Super Bowl Half Time Show outfit, packaging from the Mom’s Spaghetti fast-food brand he’d launched in the 2020s, and absolutely no imagery of him with hair dyed blond. Instead, he was represented in an idealised portrait of his middle-aged appearance – boyband lips and cheekbones decorated with a beard, lines under his eyes, expression at once grave and simmering with mischief. This wasn’t a photograph of an unwanted derailment of the 28-year-old youth icon who’d once worn those Dickies overalls and snarled into his microphone that he would kill everybody – this was the face of a charismatic, boundary-pushing modern star who had been one for a quarter century.

“You don’t want to look like you’re always looking back when at the same time you’re trying to create and move forward,” Paul Rosenberg told Billboard. “It’s a little bit of a difficult balance, and for him it can get a little frustrating. He doesn’t want to seem like he’s done being a currently recording music artist, because he very much IS. It’s just about figuring out the right way to walk that line.”

Like most great old pop stars, Eminem’s projects in the span between his late 40s and early 50s veered between these affirmations of his legacy, extracurricular side projects of various degrees of worthiness, gorgeous wins that made it impossible to believe his relevance was ever in doubt, and indefensible acts of retire-bitch washedness. Occasionally all at the same time: At the 2022 Super Bowl Half Time Show, looking ridiculous in double leather, terracotta foundation and Eugene Levy eyebrows, Eminem took the knee in solidarity with Colin Kaepernick’s protest against racist police violence despite reports that the NFL had told him not to do it. After the NFL claimed they were aware of the gesture and a round of takes came in about Eminem’s empty co-opting of protest movements, Snoop Dogg told TIDAL Magazine that Em only got away with it because Jay-Z, a diversity hire following the NFL’s nightmarish systemic racism being made public, had told them he’d walk unless they allowed Eminem to kneel. The day after, a 3rd Grade teacher named Susanna Cerrato taught her class why Eminem took the knee in the hope they would become just like him, and I cried. Now that’s the message that we deliver to little kids.

Eminem reaffirmed his appeal with little kids again, too. His ancient Encore single “Mockingbird” got rediscovered by TikTok and unexpectedly became one of the biggest songs of 2023, passing a billion streams before the end of March. Curtain Call 2 got a promo run on the in-game radio in the youth-brand soup of Fortnite; at the end of the following year, Eminem skins in both young and middle-aged appearances could be bought for player use in chainsawing down stylish superheroines and anthropormorphic bananas – a gigantic virtual Eminem performed “Godzilla” at the climax of Fortnite‘s biggest content expansion.

Eminem, by now having long branded himself as a hip-hop athlete, remained a peer of other sportsmen. He walked Terence Crawford out to his 2023 fight with Errol Spence Jr., and could be seen springing to his feet in anticipation seconds before Crawford landed the winning punch (Crawford, as a memento of his victory, was gifted a painting of Eminem). Fans videoed him playfully flipping off supporters of the San Fransisco 49ers while watching them beat the Detroit Lions in the team’s closest shot at the title for decades, serving as a funnier and more human alternative to Taylor Swift in an NFL season overpowered by her relationship with Travis Kelce – Twitter users swept up in the romantic atmosphere finally gave up complaining about his beard and lusted after it instead. He channelled his stadium persona, embodied by now in Recovery rap-rock, into a good ad campaign as the voice of Gatorade (“Greatness isn’t about what you’ve done, it’s about what you do next”), and then a bad ad campaign as the voice of Crypto.com over a year after Sam Bankman-Fried’s disastrous actions made crypto untouchable for any celebrities worth taking seriously (“Some still call it luck — let ‘em. You know what it’s always been — inevitable.”) But Eminem’s least appealing interaction with crypto was his ill-advised brand partnership with the NFT grifters/alleged kaliacc ironofascists Bored Ape Yacht Club, which saw him returning to his old habitat of the MTV VMAs, now as riddled with shameless misogynistic trolling and weird videogame scams as an unmoderated Y2K-era internet forum left up for 20 years. Hidden from view from the audience for most of the performance, Eminem rapped behind a projection screen with Snoop Dogg, while an unimpressive pre-animated video showed the characters from their Bored Ape NFTs, “Dr. Bombay” and “Bruce”, travelling the world of BAYC’s Web3 boondoggle Otherside. (Eminem hadn’t even bothered to show up for the motion capture, instead leaving Snoop to perform alongside a dancer, body paint model and gay rights activist named Matt Perfetuo; Snoop Dogg was later hit with a lawsuit for promoting NFTs without disclosing his own financial stake. He responded by launching an ice cream brand based on his Ape.)

Eminem and his team put out a second greatest hits album in 2022, Curtain Call 2, to coincide with Eminem’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction and officially end Eminem’s second act. The 2005 Curtain Call felt like death, with its intentionally hostile track ordering sickened further with the Lynchian self-nullification of “When I’m Gone” and the legacy-besmirching shitpost of “FACK”. Curtain Call 2 feels like life, but in the sense that it is a chronicle of Eminem’s post-sobriety samsara, using pinball theming to imagine his art as a kinetic body, bouncing this way and that way whenever it touches resistance. Compared to the 2005 Curtain Call, a coherent sonic experience of minor-key plastic deathmarches, Curtain Call 2 is far more eclectic, a museum of Eminem’s experiments in maintaining commercial relevance long enough to bring his rapping to ever more quixotic extremes.

Incarnated into a different body for every new project, Eminem’s voice and personality changes on every track — a veteran trick-shooter muttering under his breath; an Olympian madman with a throat too clogged up with syllables to let them out without pain; a video-nasty actor hamming it up in a thankless role by inventing new accents; a screaming paragon electrified by his own sanity; a bombing comedian cussing out his audience on a shaky viral video. Curtain Call’s sonic landscape of KORG Tritons are as early 2000s as a Flash game about killing Osama Bin Laden, but the production choices on Curtain Call 2 are so brutally timestamped that you can trace the development of 2010s chart music through them — the soft dancehall wobs in “3 a.m.” evolving into the harsher brostep squeals of “The Monster”, the radiobomb glurge of “Nowhere Fast” extinguished by the Xanned-out bells and burrs of “Lucky You”, the dick-swinging retropop of “Berzerk” counterbalancing the pandemic-era chill vibes of “Gnat”. Sitting alongside are attempts to make original sonic signatures for Eminem that he discarded in later phases, like the The New Royales-backed garage rock jock-jams or the dancehall-circus bombast of his work with Dawaun Parker. There’s even a couple of throwbacks to the style of Eminem’s first age, like “Higher” (2020 doing 2002), “Beautiful” (2009 doing 2004) and “From The D 2 The LBC” (2022 doing 2003), along with the sonic callbacks worked into the productions to make them suit an artist defined by his early 2000s, like the nose-pinch timbre to the synth strings in “Fall” (2018 doing 2000), the rimshot perc on “Not Afraid” (2010 doing 2002), and the thumpy chicka-chicka disc scratching on “The King & I” (2022 doing 1999).

Overrepresented on Curtain Call 2 is Recovery, almost half of the entire tracklist of which gets included — a justifiable choice due to its position as the first album to reach 1 million digital downloads, the first blockbuster album where every track on it both sounded like a single and was possible to consume as one. But absent are some legitimate hits, the most revealing being Relapse’s lead single “We Made You”.

“We Made You” is one of Eminem’s weirdest records, depicting the serial killer Slim Shady of Relapse as a personification of late 00s tabloid culture, paralleling his lust for the designated trainwrecks of the late 2000s with their destructive paths. It’s not clear why Eminem didn’t include it. Perhaps it was too outdated, with minimal interest to anyone other than nostalgic Perez Hilton comment section trolls. It might even have been too controversial — one of Shady’s victims in the song is Amy Winehouse, whose death two years later proved the horror that “We Made You” tried to comment on. But it’s more likely due to Eminem’s dislike of the song. He’d been so sure the song would be a hit that he’d poached the Doc Ish beat from Bizarre, and recruited Joseph Kahn, the director of the video for “Without Me”, to make a video he pitched as a direct sequel to the earlier one.

Released at a strange time when the music video as a form was in danger of vanishing, the 2002 approach seemed to cast Eminem as a relic. When Complex’s Noah Callahan-Bever challenged Eminem on why “We Made You” had underperformed, Em at first tactfully blamed its complicated flow — “I kind of liked the way the beat felt like it was slower in the chorus and then it sped up for the verses, but stepping back and looking at it as an average consumer or somebody who goes to a club, it might have been hard to figure out what the hell was going on in the song.” Later, he turned on the entire Relapse project, reworking Relapse 2 into the drastically modernised Recovery, the lead single of which was “Not Afraid”. “Not Afraid” is the turning point of Eminem’s middle career – an inspirational song which, with its puns and poop jokes, is funnier than “We Made You”, but not, you know, funny like “We Made You”. When VIBE magazine said they had visions of Eminem in a music video “dressed up like Tiger Woods and surrounded by porn stars”, Eminem retorted that he chose not to do it because it would have been “so predictable”. By the time of 2014’s “Guts Over Fear” — another legitimate hit that didn’t make the Curtain Call 2 tracklist — Eminem rapped about lacking inspiration now that his inner pain is healed, but vowed that even if all he can do for the rest of his career is rewrite songs he’s written before, “I’d rather make “Not Afraid 2” than make another fucking “We Made You””.

Even as “Without Me” became a consensus classic, one of the most streamed songs of the 2000s, Eminem stuck by his resolution. Starting from Recovery, and continuing until the Zoomer video director Cole Bennett saw the opportunity to evoke Eminem’s early work in his treatment for “Godzilla”, Eminem’s videos revolted against the “We Made You” aesthetic so strongly that almost all the colour drained from his visual presentation. Only the hazy rural Americana of Joseph Kahn’s “Love The Way You Lie”, the Instagram-filter VHS of James Larese’s “Berzerk”, and the Max Headroom Shady in Rich Lee’s “Rap God” inherit the rowdy colours of the early, funny ones. In Eminem’s old videos, Shady’s face is a visual motif, with his sinister abilities to make every person act like him and to peer knowingly through the screen into our living rooms. The most familiar image presented by Eminem in his late-2010s videos is a hooded figure in a basement or tunnel, dressed in grey or black, dancing and miming energetically in a full-body shot while the rest of the video happens without him.

Eminem certainly put out other funny songs, but they stayed confined to album tracklists, and focused more on wacky verbal constructions than on radio appeal. “Tone Deaf”, from 2020’s Music To Be Murdered By Side B was the breakout of these — with a grouchy and simplified self-produced beat, a hook about getting cancelled, a truly hideous animated video made by some NFT shithead, and a bornana, it went viral in 2022 as one of the songs of all time. Novelty single Eminem was utterly done with; any of his attempts at humour now invited mass ridicule.

Once Curtain Call 2 came out, though, anything could happen. The last time Eminem had put out a Curtain Call, he’d come back skinny-ripped, with an eyelid twitch, and speaking in a weird accent. Curtain Call 2 closed this second act, this messy and strangely spiritual journey back towards himself. The tightrope out of twine Eminem talked about on “Walk On Water” had become a Gordian knot. His only viable move to formally begin his third act was to do something that nobody expected he would do, yet something so familiar that even people who’d abandoned him after Revival would see his old genius was still in there. It had to be something that would reach out of the core hip-hop audience and appeal to the casual fanbase, maybe people who’d tuned out of a chart full of unobtrusive hypopop, Black artists claiming anxious-interval stomp-clap-hey sounds, and Taylor Swift’s gruesomely overexposed Millennial greycore mixtape The Tortured Poets Department, but at the same time, mean something to kids enthralled by Kendrick’s vicious but playful diss track “Not Like Us”, the facetious lyrics of Sabrina Carpenter, and the baggy Y2K fits and bandanas of Billie Eilish. Eminem could no longer rely on the old media landscape to help him — Interscope had fired their entire radio pluggers and promoters department earlier in 2024, and as a man now in his 50s Eminem had aged out of being what a radio programmer would choose to attract a youthful demographic demanded by their advertisers. Eminem had to stand by the post-sobriety accomplishments that meant so much to him and to many of his fans, but at the same time, do that by making a symbolic break with the path he’d started on by foregoing a novelty lead single for Recovery 14 years earlier. He had to avoid both the death of being discredited and the death of becoming an institution. He had to remind people of who he was, yet at the same time use sleight of hand to make over a decade of his career disappear.

How could anyone possibly do all that in under four minutes? Maybe they’d need to be able to do magic. Or maybe they’d just need to make it look like they might be able to.

- Greene is clearly describing the Eminem from the “Not Afraid” video here, who only looked like that because he had an exercise addiction at the time and the video was being shot with the sun in his face. While Greene presumably meant it to be true on more of a vibe level, it still deserves mention just how much the Eminem of “Walk On Water” is not gaunt or mean-eyed at all – having gained weight, he’d restored the pleasing softness to his face he had back when he made “My Name Is”, and his vulnerable stage mannerisms made his eyes always round and plaintive, like the eyes on the 🥺 emoji. Revival‘s fans – which do exist, and are generally older women – often report finding Eminem’s new look and stage presence to be a significant part of the era’s appeal. After being very ‘other’ and aloof for a half decade, Revival saw the Rap God take off his halo to become mortal, with the capacity for warmth and sexuality that this implies, too. If it had been the icy blond alien of The Marshall Mathers LP 2 who made “River”, it’d be hard to imagine Em’s performance in the video being as effective as it is.

↩︎ - Someone I showed this to said I should probably give a little bit of background info about the circumstances of Harry Houdini’s death, seeing as it happened even longer ago than things I do cover in this piece, like Johnny Cash rapping about chickens, or Eminem getting critical respect. I love the story, so here it is:

Houdini, by 1926 heralded as one of the greatest entertainers of all time and focused more on his anti-spiritualism activism, performed in Montreal. Having to abbreviate his show after dinging his ankle doing one of his stunts, he used the extra time to invite some young fans from McGill University for a meet-and-greet. In awe of him (despite Houdini’s promotion of skepticism, the belief he had actual magic abilities was wide), an idiot known as J. Gordon Whitehead asked Houdini if he really was impervious to blows to the stomach (accomplished in his stage act by abdominal clenching). Houdini replied that he was, at which point Whitehead repeatedly socked Houdini in his internal organs before he had time to react, rupturing his appendix. Despite severe pain and sepsis, Houdini got on the train to Detroit to perform at the Garrick Theatre. After his show – an athletic feat even for someone who wasn’t dying, and I’ve HAD sepsis so I know – Houdini collapsed just after the final curtain fell, and was rushed to hospital. He died on October 31st, at 52 years old, the same age Eminem will be on October 31st 2024. Some believe Whitehead was an agent of the spiritualists, sent to murder Houdini for his attempts to outlaw mediums as confidence tricksters. It’s more likely he was just some fucking dick.

By the way, people in Detroit still hold seances to try and contact the ghost of Houdini every Halloween, in reference to a spiritualist-trolling statement by Houdini that his ghost would visit anyone who tried to speak with it. His anti-spiritualism also got him into a beef with Arthur Conan Doyle, who used to be a good friend of his, but who was an ardent spiritualist after seeing what he believed to be his deceased son’s face in a photograph. And we all know how ridiculous that sounds, since Arthur Conan Doyle’s greatest literary creation is an embodiment of analytical thought and scepticism, but photographs were a brand new invention that emerged during Doyle’s lifetime, so to him this seemed like the most objective evidence made with the most cutting-edge equipment. If ACD was around today, he’d be one of those credulous dipshits who thinks ChatGPT can think.

↩︎ - Mark Douglas did, later, do a parody of a 2017 Eminem as one of the last songs for his channel The Key of Awesome. It’s tepid as a piece of comedy, especially compared to how funny and mean his “Not Afraid” parody is, but the joke goes into a different direction to the more condescending parodies by younger comedians that were more popular by that time. Unlike the mean, neurotic hypocrite at war with his own reflection that Douglas played in his version of “Not Afraid”, Douglas’s 2017 Eminem is grouchy, but right about everything he’s saying. He’s a not-quite-nice liberal suburban Dad, shaking his head at – of all things for Eminem to object to – insensitive jokes (“And don’t be ‘Too Soon!’-costume guy! ‘I’m Harvey Wine-stain!’ And it’s a pun? Please die!“), such a catastrophic character choice as to make it worthless as a piece of parody. Notable too is the fact that the impersonation doesn’t bother to even approximate Eminem’s 2017 rapping style or production, instead relying on the clattering off-beat flows, nose-pinch voices and stride pianos of Eminem’s Y2K South Park rap. With different production choices, essentially everything funny about the video could have been done as Slick Rick, or as a College Dropout-era Kanye West.

It seems most likely that Douglas, who’d only been pushed into the pop music parodies due to the unexpected success he’d had with his Ke$ha spoof “Glitter Puke”, wanted to do a normal comedy video, but with a chart parody connection to please the subscribers via embodying Eminem (one of the few big pop stars his own age, and clearly the one he most identified with). Following the Halloween theme of the channel’s ancient “Trick & Treat Or Die” song, the whole video was a retreat into comforting nostalgia – unsurprisingly, Douglas closed the channel four months later, citing mental health problems and burnout. He doesn’t appear to have done much since. His videos were really important to me when I was younger – I hope he’s doing OK.

↩︎

Leave a Reply